Although state constitutional law has proven to be less of an important source of free speech protection than some hoped or predicted after the PruneYard decision, 9 courts in New Jersey, California, and a number of other states have for many decades now interpreted state constitutional guarantees of expressive freedom to confer rights that the First Amendment does not confer. The result is that speakers and listeners can, and sometimes do, receive more protection for their speech, press, and expressive association under state constitutional law, state and federal statutory law, and state common law than they do under the First Amendment. Robins, 7 the Court similarly concluded that state constitutions might provide “rights in expression” that are “more expansive than those conferred by the Federal Constitution.” 8 6 A few years later, in PruneYard Shopping Center v. NLRB, 5 the Court made clear that “statutory or common law may in some situations extend protection or provide redress against to abridge . . . free expression” even when the First Amendment does not do so.

This is because, as the Supreme Court has recognized, the federal courts do not possess a monopoly over the interpretation and enforcement of the rights to freedom of speech and press or the penumbral right of association.

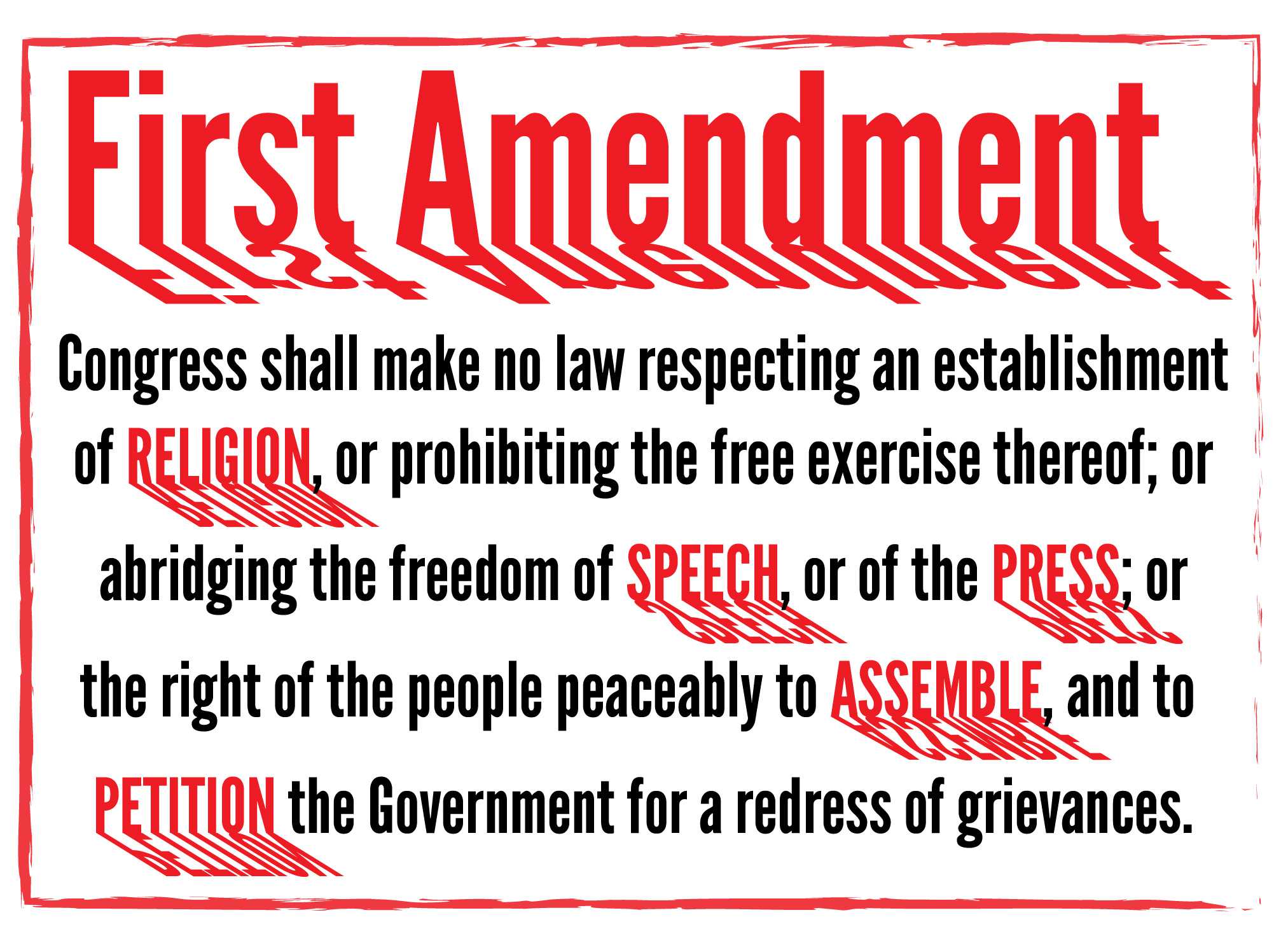

It is nevertheless a mistake to presume that the only legal mechanism that protects freedom of speech in the United States is the First Amendment. 4 Like the sun, the First Amendment’s size and brightness tend to blot out all else. 3 They also make it easy to equate the free speech tradition in the United States with the First Amendment tradition. 2 The strength and size of the modern First Amendment have given it a powerful cultural status. Today, the First Amendment protects not only explicitly political speech and journalism but also religious speech, artistic speech, scientific speech, most forms of popular entertainment, nonobscene pornography, commercial advertisements, and even nude dancing. It has been interpreted to apply to a dizzying variety of kinds of speech and expressive conduct. 1 The Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment has for decades now served as one of the most powerful mechanisms of individual rights protection in the Federal Constitution. It is easy enough to understand why discussion of freedom of speech and press has tended to be so First Amendment–centric. If one takes a look at the tremendous amount of writing that has been produced to analyze, celebrate, or deplore how expressive freedom has been legally guaranteed in this country, one will quickly see that the vast majority of it focuses on the Free Speech and Press Clauses of the First Amendment and the judicial opinions that interpret and give those clauses force. The First Amendment dominates both popular and scholarly discussion of freedom of speech in the United States. The result is a deeply inconsistent body of First Amendment law that relies on a false view of both our regulatory present and our regulatory past - and is therefore able to proclaim a commitment to laissez-faire principles that, in reality, it has never been able to sustain. Missing from the Court’s understanding of freedom of speech is almost any recognition of the important nonconstitutional mechanisms that legislators have traditionally used to promote it. And yet, the Court’s view of the relevant regulatory history is impoverished. This is because in few other areas of constitutional law does the Supreme Court look more to history to guide its interpretation of the meaning of the right. Recognizing as much is important not only as a descriptive matter but also as a doctrinal one. It also makes evident that the contemporary system of free expression is much more majoritarian, and much more pluralist in its conception of what freedom of speech means and requires, than what we commonly assume. It reveals that there was more legal protection for speech in the nineteenth century than scholars have assumed. Doing so changes our understanding of both the past and the present of the American free speech tradition. This Article explores the history and present-day operation of this non–First Amendment body of free speech law. A rich body of local, state, and federal laws also does so, and does so in ways the First Amendment does not. Yet it is not the only legal instrument that protects expressive freedom, the rights of the institutional press, or the democratic values that these rights facilitate. The First Amendment dominates debate about freedom of speech in the United States.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)